The US rose over the last decade to become the world's largest oil producer. Does the pandemic spell the industry's decline?

Texas oilman Allan P Bloxsom III still remembers the taunts of "college boy" that greeted him on the offshore drilling rig where his father, desperate for his wayward son to shape up, sent him to work one summer.

"Against my wishes I went and it changed my life," says Mr Bloxsom, now 63 years old and the president of Fort Apache Energy, a small company that operates oil and gas wells in Texas and Louisiana. "I was hooked."

That was decades ago. Since then, his home state of Texas has more than doubled its crude oil output, helping to turn the US into the world's biggest oil producer.

But as oil prices tumble - briefly falling below zero in a first last month - following a dramatic drop in energy demand because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the industry is going into reverse.

Giants such as Exxon and Chevron and fracking firms such as Diamondback Energy have shut in wells and slashed investment in recent weeks, helping drive down US crude oil production by nearly one million barrels per day from March to April - the third largest monthly decline in a century.

Mr Bloxsom cut his typical output of 800 barrels per day by more than half. Others have gone even further.

"Right now everything I have is shut down. Everything," says Bill D Graham, president of Midland, Texas-based Incline Energy, which has 80 wells that in more typical times would about 275 barrels per day.

The supply cuts are not unique to the US.

The International Energy Agency expects global oil supply to fall to a nine-year low this month, as producers around the world reduce output in response to prices that dropped by more than two-thirds in April before starting to stabilise.

But even before the coronavirus pandemic hit, the industry was experiencing a supply glut - driven by the US boom - that had depressed prices and prompted strains in oil-producing Texas and elsewhere. The Wall Street money that helped power the fracking growth had grown harder to come by, while big firms were promoting investments in renewable energy.

Forecasters at IHS Markit say supply is unlikely to return to 2019 levels until at least 2023. There is a chance that 2019 will have been the high point for global output, should the pandemic permanently reduce energy demand - for example, by increasing telework and reducing business travel.

"This is a transformational crisis for the world and what happens to oil will be shaped by the broader forces of change that are coming out of Covid-19," says Jim Burkhard, the firm's head of oil market research.

"There's enough of these variables in play where you don't have to have a doomsday view of the world to consider that oil demand could have peaked in 2019. That's not our base case, but it is our alternative scenario."

In the US, several large US companies have already filed for bankruptcy, with more expected in a sector where debt levels were already dangerously high. Services firms, desperate to survive the crisis, have cut more than 66,000 jobs - almost 10% of total employment - with more reductions likely, the Petroleum Equipment & Services Association industry group estimates.

As healthier businesses scoop up the assets of distressed rivals, the industry is likely to emerge with fewer firms and fewer workers.

"The future for the small operator like me - I see it going away completely," says Mr Graham.

Mr Graham, whose father started Incline Energy in 1966, says he managed to keep his five staff after securing government coronavirus rescue money. But if the price his oil fetches - which for now is lower than figure traded on financial markets - does not bounce back above $25 by October, those jobs are at risk.

"With the wells shut in and zero income, we're just going to have to play a waiting game and see how long we can last," the 66-year-old says.

US President Donald Trump has pledged his support for the oil industry and opened government storage facilities, so that producers do not have to sell at a loss due to lack of storage as happened in April. The Federal Reserve has also adjusted its coronavirus relief programmes to make sure energy firms qualify.

But Democrats, backed by environmental groups and others concerned about fossil fuel contributions to climate change, have resisted greater assistance for the sector, pointing to already high debt levels among many firms. "It is deplorable to send good money after bad," Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey, wrote after the Fed's changes.

Leslie Beyer, president of industry group Petroleum Equipment & Services Association, says many of her members are already working on renewables and cleaner energy technology. She calls those who hope the pandemic will spell the demise of the industry "misguided", noting that global population growth and economic development in poor countries will drive continuing demand for oil.

"Some people who don't understand the way the industry works ... think now is the time to transition entirely to renewables. There is definitely room for renewables and we need to increase those, but we don't go zero to 60," she says.

"It's important that we don't give up on the ingenuity that created the shale boom. That's what put us in the great position that we're in as the world's largest producer ... We need to maintain that."

But the best days of the industry may be over, Mr Bloxsom says, pointing to the scarcity of young people at conferences.

"I have told all four of my kids, 'Do not go into the oil patch," he says. "Do something else."

After sales service: Visiting client's mining plant in Burma

After sales service: Visiting client's mining plant in Burma

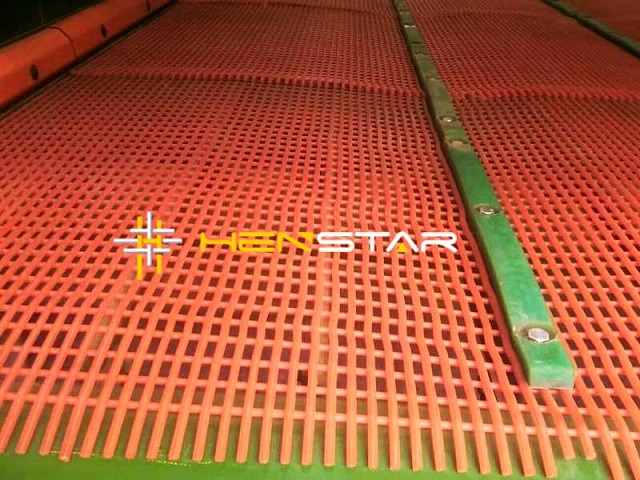

TPU tensioned screen mesh

TPU tensioned screen mesh

Mining companies may pause growth plans amid Ukraine war, inflation

Mining companies may pause growth plans amid Ukraine war, inflation

Coal export ban in Indonesia.

Coal export ban in Indonesia.